Mott Gristmill

There is something about gristmills and waterwheels that resonates with just about everyone. The gristmill is an American icon that evokes sentiments of home and community, as is evidenced in the gristmill pictures so many of us have in our homes. Perhaps some of this sentiment was at the heart of our efforts in 1999 to relocate a historic working gristmill to our community in Texas. At the time we had an electric-powered mill running in a small outbuilding, but we wanted an authentic waterwheel-driven mill where we could grind the grains we grew into flour for both our families and our neighbors. So, the search was on, and it took us once again back to the East Coast where we tracked down an old, dilapidated gristmill in the town of Califon, New Jersey.

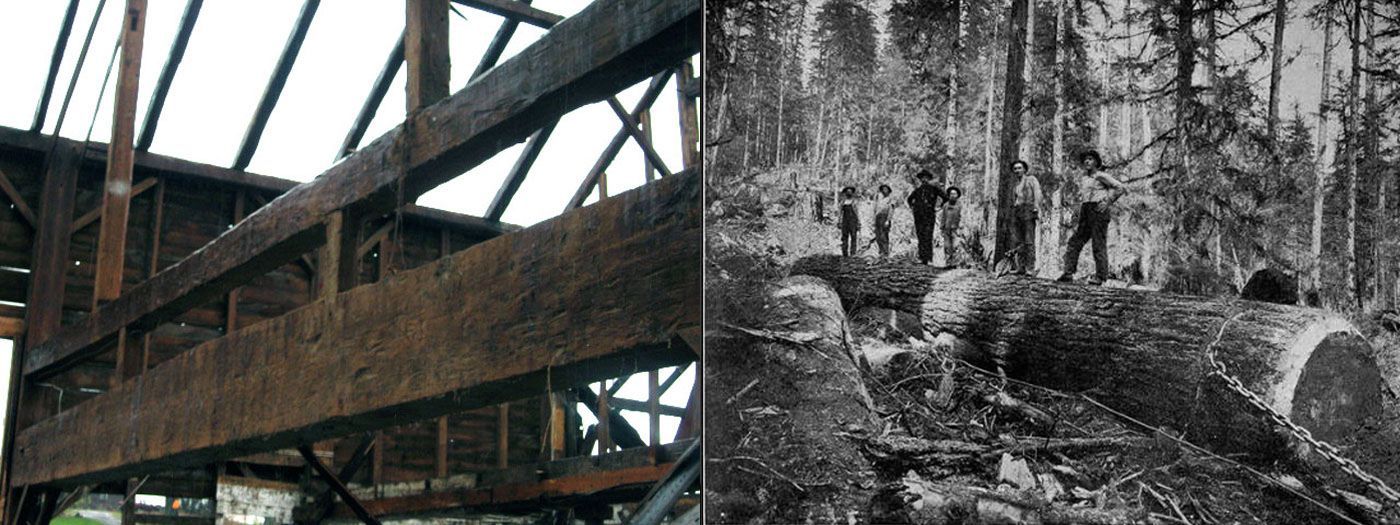

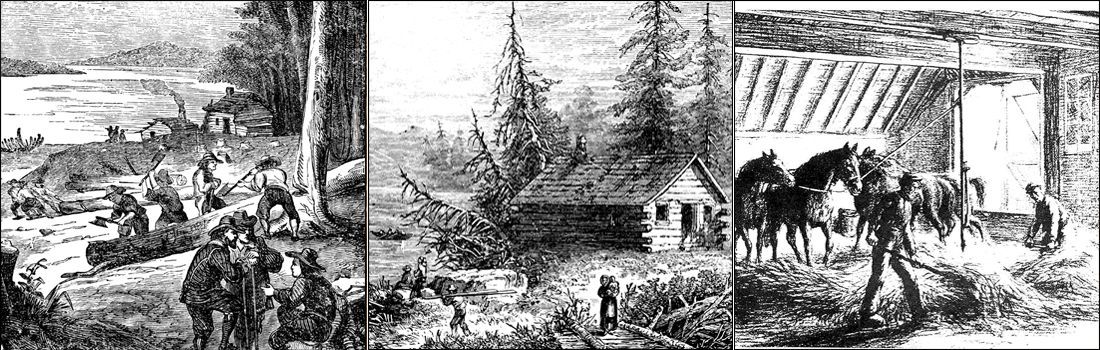

This area of New Jersey is not only noted for its rural beauty (New Jersey is, after all, “The Garden State”), it was also the scene of some of the most dramatic events in the American Revolution, events that, as we’ll see, were directly related to the Mott mill. When I first visited the mill, I was told that it dated to about 1820. But on closer examination we found that it was actually a much earlier gristmill that had been altered, as were many other mills during the transformative years of the early Industrial Revolution. We determined that the mill had been lengthened twelve feet and the roof raised a story. In October of 2000, we carefully dismantled the mill and shipped it to Texas. After moving the mill and re-erecting it on The Ploughshare campus as the Homestead Gristmill, we began to gather more information about its history. A land deed from 1768 is the earliest written record of this mill. The deed records: “Beginning at a large white oak marked for a corner standing near a small swamp on the southwest side of the brook below the mill . . . .” The deed was written when a German immigrant named Asher Mott decided to sell his share of the family property to his older brothers, John and Gershom for £ 1,000.

Further research revealed that John Mott was a patriot of some note. Living and running his gristmill in the Long Valley of west central New Jersey, he adhered to the patriot cause, and when the American Revolution broke out in 1775, he enlisted as a captain in the local militia. New Jersey is known as the “crossroads of the American Revolution,” as both armies traversed it several times.

In 1776 things did not fare well for General Washington and his army. He had been consistently outgeneraled and defeated by his adversaries, British generals Howe and Cornwallis, at the battles of Long Island, Manhattan, White Plains and Fort Washington. At Fort Washington he had watched from across the Hudson River as British troops surrounded his namesake fort on upper Manhattan and forced it to capitulate, sending all 4,000 defenders to prisons. As if this were not enough, the next week he was surprised by Cornwallis, who skillfully executed a night march and nearly succeeded in surrounding and destroying his ragged army.

In their haste to escape, Washington’s men left their breakfasts boiling in kettles over campfires for the British troops to enjoy. Through a cold rain, Washington’s army retreated down the length of New Jersey to the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. By that time the army had dwindled to not many more than 1,000 tired, discouraged, hungry, ragged men. Cornwallis, leisurely pursuing Washington to the Delaware River bank, dismissed Washington and his rabble with the comment that he would “bag the fox in the morning.” Five years later, of course, “that fox” “bagged” Cornwallis at Yorktown, ending the American Revolution with this British defeat.

But at that point in 1776, Washington’s back was up against a wall, and he knew that he had to have a turn of events or all would be lost. So, taking a gamble, he planned a surprise attack on Cornwallis’s outpost across the Delaware River at Trenton, New Jersey. But to get across the river and through the countryside back roads at night required a knowledgeable, local guide.

This is where Captain John Mott came forward. On the night of December 25, 1776, counting on the enemy being off guard after their holiday celebrations, Washington led his scraggly army—guided by Captain Mott—across the ice-flow-choked Delaware to capture the post at Trenton. They endured a grueling river crossing, a night march, a battle pitched at sunrise and a countermarch back across the river. Most of this time they were pelted by snow and sleet as they marched through a snowstorm in which many of the men did not have shoes, and the rags they wrapped around their swollen feet were soaked through with blood.

A week after the Battle of Trenton they again crossed the river to fight the Battle of Princeton, after which Washington led his army into winter camp at Jockey Hollow in Morristown, New Jersey, not far from Captain Mott’s gristmill. The mill undoubtedly served as a source for their flour for the rest of the war, including the winter encampments at both Valley Forge and Jockey Hollow. If you have ever visited New Jersey in the winter, you know that it is not the season for a camp out. The winter weather can be severe, ranging from cold rain to deep snow and often a combination of both on the same day. One can imagine the winter conversations that went on in the mill as they ground corn and wheat into flour, while debating which side would prevail in the conflict.

After the Revolution, John Mott went on to grind grain for the local community, and the mill passed through several hands during the 1800’s. It finally closed about 1920 when the post–World War I recession and competition from larger mills made it obsolete. Today, most all of the flour milled in America comes from five huge mills that use a steel hammer milling process that actually smashes the kernels.* Stone grinding has gone by the wayside, except at mills like our Homestead Gristmill where you can still get fresh, stone-ground flours.

Published in SustainLife Quarterly Journal (Fall 2012)