The Great Epizootic of 1872

An Example of Large-scale Vulnerability from the Past

People often ask what interesting things we find in the centuries-old barns we dismantle for our barn restoration business. Well, there are a lot of interesting “things,” like the time we found an old pillowcase hidden in a corner of the first barn that we took down that was full of jewelry from a long-forgotten house burglary, and the time we found the bowling ball that my helper claims is the ball that old Rip Van Winkle used before he drank the potion that put him to sleep for twenty years in the Catskill Mountains. And there are also occasionally some very interesting writings, most often in the form of centuries-old graffiti. About 1870, a black ink feed sack marker came into use that seems to have found its way into the hands of just about every boy and hired hand in that era. For the next twenty years they made it their off-hours pastime to write their names, dates and musings on barn interiors. Unlike the modern railway boxcar graffiti that we are all subject to while waiting for freight trains to pass through town, this barn graffiti was often scrolled in the most eloquent of nineteenth century scripts.

We recently found perhaps one of the more intriguing examples of such writing in a barn from the Mohawk Valley of New York. It read simply:

“Equine flu epidemic, October 10, 1872”

This example tweaked my curiosity, as I thought that if this was a significant enough epidemic to make note of on a barn wall, it might have made its way into the history books. So I did some speedy research and found that the 1872 horse influenza epidemic was indeed historic. But what I found most interesting is that this catastrophic event remains forgotten and entirely unknown to most of us today, probably because horses play such an insignificant role in our modern lives, unless, of course, you—like us—still depend on them for plowing and cultivating the fields which produce your food.

Horse flu is formally known as equine influenza. When a disease that affects animals reaches widespread proportions, it is known not as an “epidemic,” but an “epizootic.” Equine influenza is a highly contagious virus occurring globally that has been known to infect up to 100% of exposed horses, though there is now an effective vaccination for it. Unlike swine flu or avian flu, it has not spread to humans in the past, though it did have tremendous effects on people who at that time depended completely on horses for transportation, delivery of their food and firefighting.

Beginning in Toronto, Canada, in the late summer of 1872, in only three days the disease hit nearly all the livery stables and the horses used to pull streetcars in that city. By mid-October, horses in all of Canada, Michigan and the New England states were infected. By the beginning of November the disease had spread to Illinois, Ohio and South Carolina. By the end of the month, Florida and Louisiana reported cases.

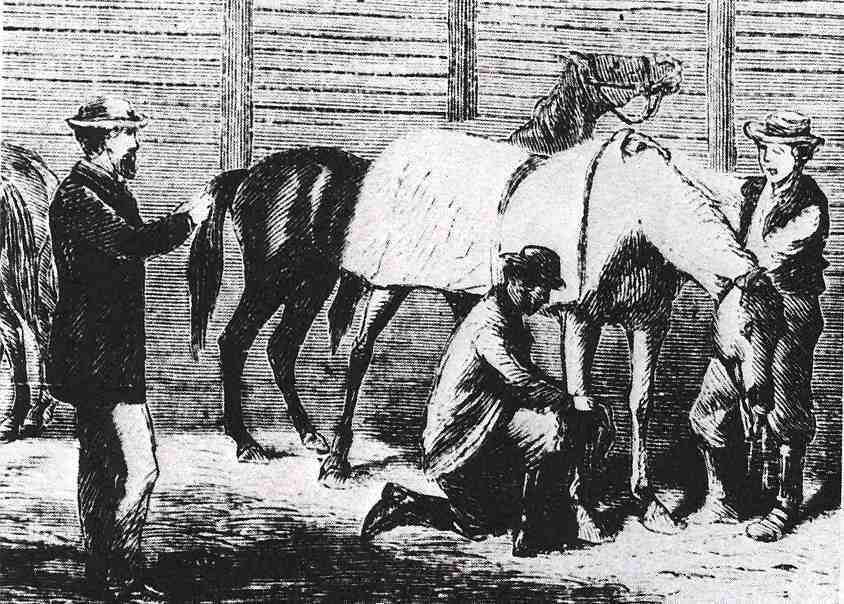

The epizootic spread across America from New England to California in only ninety days, and as far south as Havana, Cuba. It became known as the “The Great Epizootic of 1872.” Nearly 100% of horses in its path were infected, and between one and ten percent died. Most infected horses could not stand up, and when they could stand, they coughed violently. The disease rendered them unable to do any work, carry riders or pull wagons and carriages. All commerce ground to a halt as the most widespread and devastating equine flu epizootic in history took both Canada and the United States by surprise.

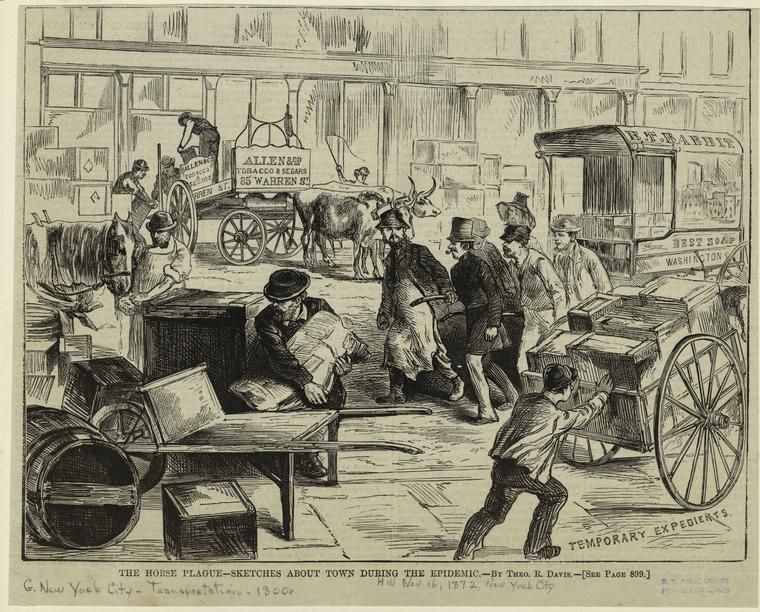

The coal needed to fuel locomotives could not be delivered. “The outbreak forced men to pull wagons by hand, while trains and ships full of cargo sat unloaded, tram cars stood idle and deliveries of basic community essentials were no longer being made.” The epizootic contributed to the financial panic of 1873, and it even affected the war in the West with the Apache Indians, where neither the Apaches nor the US calvary could use their horses and resorted to fighting on foot.

In November of 1872, a great fire broke out in Boston that destroyed 776 buildings across 65 acres of the city. Because of the epizootic, horses were unfit to pull the fire engines, hose reels and other fire equipment, so crews of men were organized to pull the heavy fire equipment on foot.

Newspaper headlines of the day reflected the widespread panic: “Alarming Effect upon the People, Total Suspension of Travel, Disappearance of Wagons.” In October 1872, the New York Times reported:

"There is hardly a public stable in the city which is not affected, while the majority of the valuable horses owned by individuals are for the time being useless to their owners. It is not uncommon along the streets of the city to see horses dragging along with drooping heads and at intervals coughing violently."

A few days later the Times reported:

"Large quantities of freight are accumulating along the Erie Railway in Paterson, New Jersey. The disease is spreading rapidly in Bangor, Maine. All fire department horses in Providence, Rhode Island, are sick."

Everyday conveniences that had been taken for granted disappeared.

That a horse disease could cause such a nationwide catastrophe and contribute to a financial panic and prolonged financial downturn might be difficult for us to imagine. The Equine Flu epizootic of 1872 almost seems like a quaint, forgotten, historical footnote on how much things have changed, including our once-total reliance on draft animals. But this historical footnote begs an obvious question: Though we do not rely on horses today, have we become even more dependent on other forms of transportation that are totally dependent on a vulnerable fuel supply? Some people may be confident that our modern, global system is more resilient and robust than the draft animal–dependent system of the nineteenth century. But our modern system is much more fragile due to its ubiquitous dependence on one source of fuel that is almost completely out of our ultimate control, with 80 percent of our transportation fuel being imported.

From its very beginning, the Transportation Revolution of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries went hand in hand with the Industrial Revolution to completely reshape our economy and lifestyle, especially in the way food was supplied. This revolution began with the age of canals in the 1820’s, which radically lowered shipping prices. The age of canals was followed by the age of rail, which gave way to the age of highways after World War II. And now the Transportation Revolution continues with global shipping on container ships and dependence on oil tankers. In a previous issue we reported that the average American meal travels 1500 miles to the consumer, and many states grow as little as 15 percent of their food.

If the modern equivalent of the equine influenza epizootic were to strike, we are actually in a far more vulnerable place today than the America of 1872, which was still a largely agrarian economy with a rural population for which most food sources were local and therefore insulated from such a disaster.

CuChullaine O’Reilly, of The Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation, an organization which did a three-year research project on the equine influenza epizootic, concluded:

"Imagine a transportation disaster that within 90 days affected every aspect of American transportation, everything Americans took [for] granted, everything that ensured their safety, every city, town and village where they lived and left everything in its path under siege."

At the height of the equine flu epizootic, in November 1872, a writer for the New York Times wrote:

"What will be the effect of even a temporary withdrawal of the horsepower from the nation is a serious question to contemplate. Coal cannot be hauled from the mines to run locomotives, farmers cannot market their produce, boats cannot reach their destination on the canals"

Perhaps today, as the New York Times writer suggested one hundred and forty years ago from a greatly more self-sufficient and sustainable world, we also should seriously contemplate what we take for granted, and take the steps needed to provide sustainable resources for ourselves, our families and our communities.

Published in SustainLife Quarterly Journal of the Ploughshare Institute for Sustainable Culture (Fall 2012).