The Joinery Trade

We just completed another timber framing class here at Ploughshare in which we built a new timber frame of a 24 x 24 building.

This is a three-day class that has bit off more than it can chew in three days and which we need to expand to at least five days. The class calls for a lot of hand joinery, that is, hand-chiseling and sawing. What all of us notice in this class is how sore everyone is after a day of this kind of work, so the conversation inevitably evolves to comments about how strong those early timber framers were and, even further, what kind of people they were.

Who Were They?

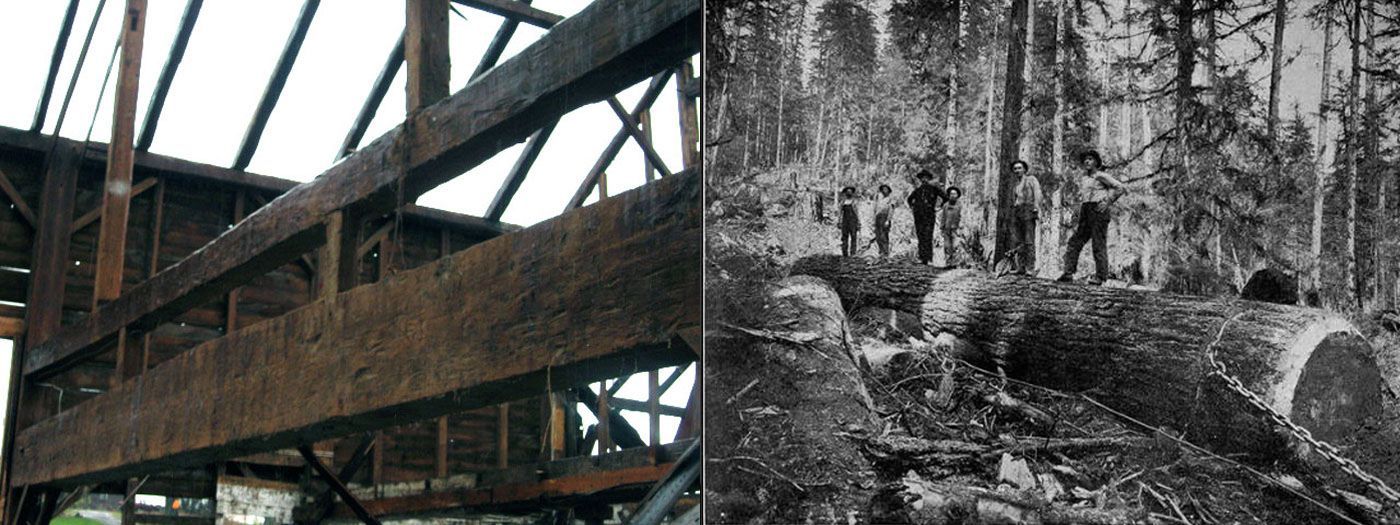

In answer to these questions, we know that timber framing was not for the weak of heart or muscle, probably reflective of the trade of house stick framing today in which it is rare to find an old man or a weak young man. Before the age of mechanization, (i.e. saw mills) there were no short cuts, and it appears from the quality of the timber frames extant from this pre-industrial time, care and quality ruled. The mentality prevailed that if you were going to do it, you may as well do it right, and this adage equated to longevity.

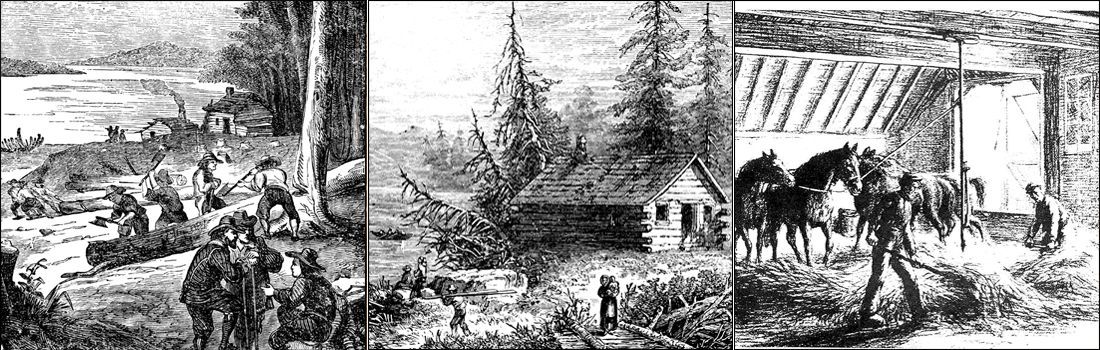

The question is often asked, “Who were these men?” and “Did the farmers build entire frames themselves?” I will offer an answer to this question based on my experience and knowledge, but open to whatever anyone else may venture. Prior to the industrial age (c. 1800) and the heavy settlement of the original colonies in America, we were a country of 98% yeoman farmers. Considering all the other trades, this did not leave much room for a large pool of free-lance timber joiners. And I think that most timber frames, which included all types of buildings, were built by the local farmers for their own farms, perhaps with help from their more experienced neighbors. (This was also supplemented by slave labor both north and south, remembering that northern states not only had slavery, but in some cases more slaves, as in the case of New Jersey, than many southern states.)

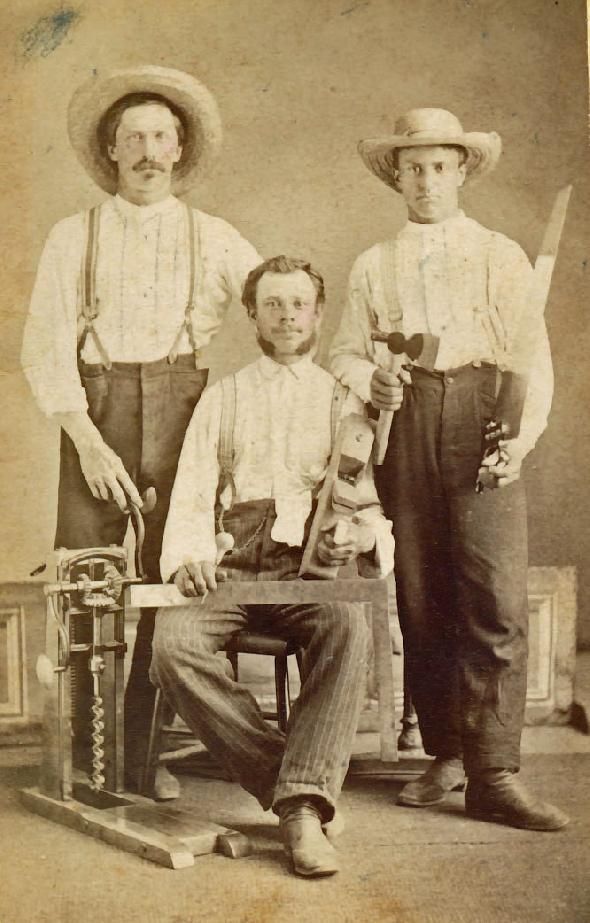

The art of joinery was, out of necessity, known and practiced by most farmers. It took just a few tools: axe, saw, auger, string line, knife, or some sharp metal object, sharpening stone, mallet and chisel. An adze and slick would also have been helpful. And some of these could have been borrowed from a relative or neighbor. So, it was these farmers who built their own timber frames . . . with some neighborly help. Perhaps this is evidenced in the wide variety of sizes of barns and homes and how no two are identical. This may come as a surprise to us moderns, but only because we have lost so much of our “handy-ness” and common sense, that was in such abundant supply with our ancestors.

But with the advent of the industrial age came its hand-maiden: specialization, something that was first more common in Europe. With industrialism, all trades began to exit the home and splinter into specialists. The cloth making art fragmented into spinners, weavers, fullers and dyers. And with time, husbandry abandoned its diverse roots and farmers specialized their crops and livestock: dairy men, orchard men, grain. Mono culture was ultimately approaching on the horizon. And the art of timber framing specialized into the joiner’s trade.

The way the business evolved, would probably be similar to what we have today when a homeowner contacts a carpenter to remodel his home. A farmer would seek out a joiner, whose reputation in a localized society would probably already be well-known to him. And they would strike a deal. Very often, the farmer would fell the timber from his woodlot and sled them down to the building site in the winter. He may also take the timber frame building process to the point of hewing the timbers square, leaving the joiner to cut them to length and fashion all the joints. The joiners also had apprentices, sons or helpers who accompanied them. But always the master joiner called the shots. The successful outcome of the frame was solely his responsibility.