Colonel Drake Saves the Whales

From time to time, in my travels in the Northeast, I pass through the sleepy hamlet of Greenville, New York—just another rural American village on the landscape of formerly thriving agricultural communities. Over the last eighty years, such communities have undergone a relentless depopulating, as generations of young people abandoned their agrarian roots and made their ways to urban centers that offered more “economic opportunity.” In our travels, we have all likely noted this scenario: boarded-up main streets with few businesses left, other than maybe a video store, tattoo parlor and a used comic book shop. The shops that once provided essential products and services have long departed, washed away by the rising tide of superstores that squat on the outskirts of town, often in what had previously been a productive hayfield. The only remarkable feature left to such towns is the nineteenth-century architecture, which in the case of Greenville includes several Greek Revival and Victorian masterpieces that now look shabby, with peeling paint and other signs of recession-induced neglect. You can also see an empty church or two. These have now passed into their afterlives as community centers or jazzercise establishments.

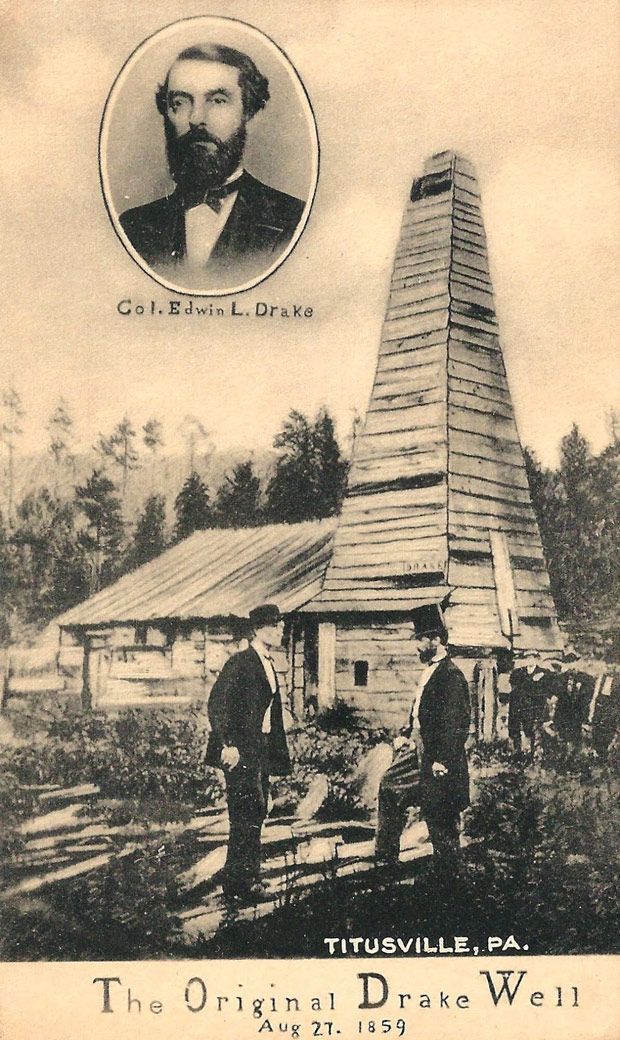

At the center of Greenville stands an unnoticed and unread cast-iron historical plaque (“placed by the authority of the Historical Commission of the State of New York, The Honorable Hugh L. Carey, Governor”) dedicated to Colonel Edwin L. Drake. Drake is the man who did more to save the whales than probably any other man ever did. His birthplace, this historical marker informs us, lies a mile or so to the north, which happens to be under what is now a supermarket parking lot.

Edwin Drake (who came to be known as “Colonel” Drake) was the Greenville local-boy-makes-good. In 1858, he migrated to the adjacent Quaker state town of Titusville, where he drilled the first commercial crude oil well. Drake’s first well was housed in a rather unusual building that bore little resemblance to a modern drilling rig, save for its obelisk-shaped wooden tower at one end. The title “Colonel” was added to Drake’s name by Drake and his business partners, in hopes of impressing the people of Titusville. This was an effort to overcome the local perception of Drake’s well-drilling operation as something of a joke, referred to as “Drake’s Folly.”1

Before learning about Drake, I didn’t associate Pennsylvania with the oil business. From what I had known, crude oil belonged more to the realm of states like Texas and Oklahoma. Actually, in those early days, Pennsylvania produced half of the world’s oil before the great oil boom in east Texas in 1901.2 Prior to Drake’s technological breakthrough in crude oil drilling and its subsequent refining into kerosene, early nineteenth-century lamplight came from homemade tallow candles and a steady flow of whale oil. This demanded that a substantial supply of whale pods be hunted down, harpooned and their blubber rendered into oil on the high seas. By drilling the first oil well, Drake saved the whales from their inevitable extinction at the hands of globe-trotting Yankee sea captains.

Yet, ironically, one of the direct descendants of Drake’s first oil well is the BP wellhead located one mile below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico. As you probably know, last year, in the wake of an offshore oil rig explosion, this well spewed gobs of crude onto the shores of our southern Gulf states, causing an environmental disaster in the Gulf. This region had already been laboring under the burden of a 2,500 square mile dead zone, also induced by our dependence on oil, as the runoff of petroleum-based chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides drain down the Mississippi River from the once-fertile heartland of the Midwest.

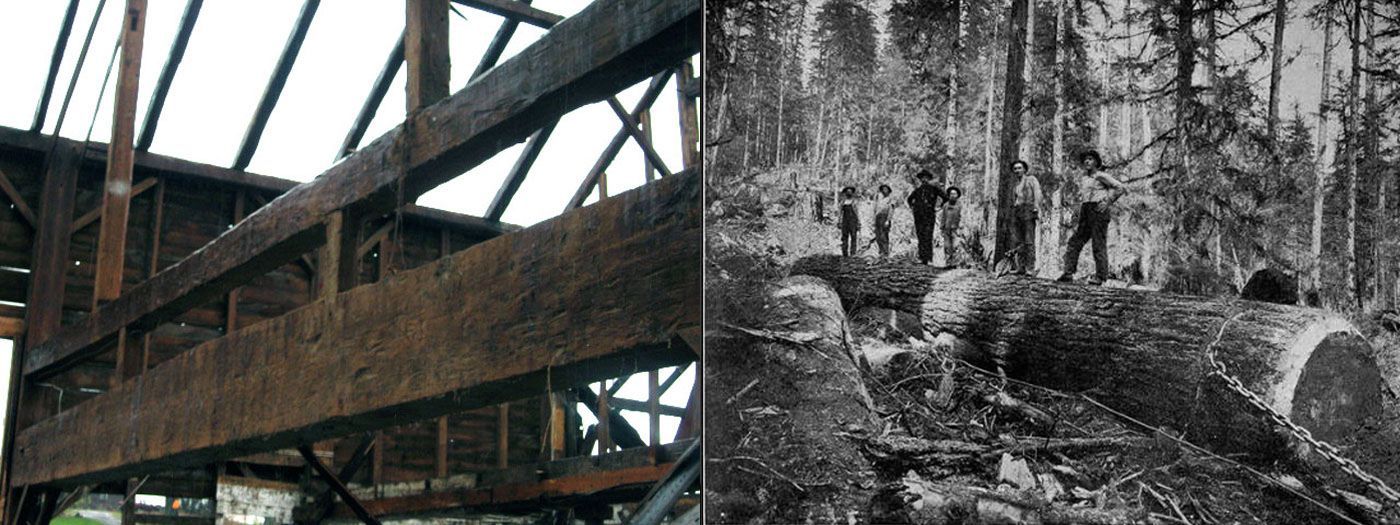

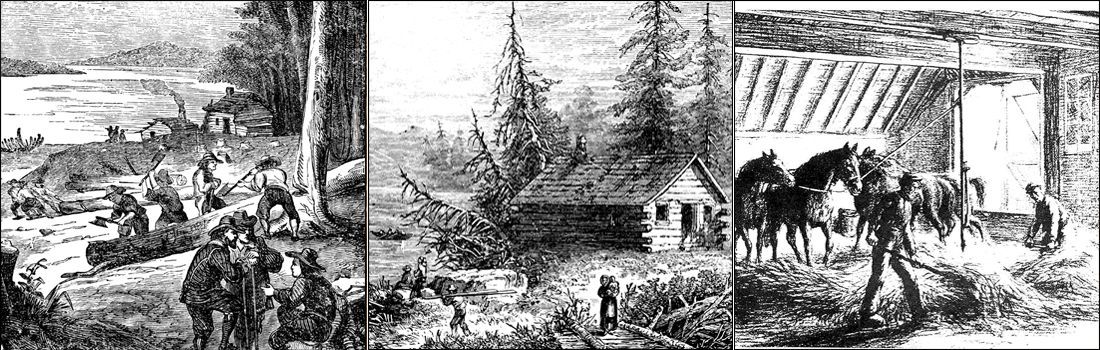

Prior to Drake’s drilling of the first oil well, the world’s main source of fuel was wood. With the rise of industrialism and urbanism, entire regions and countries had been deforested, including all of England, and by 1860 much of New England. Along with domestic heating and cooking, steam engines and iron furnaces had a voracious appetite for wood. Firewood cutters and colliers traveled far and wide in their search for cordwood and charcoal.

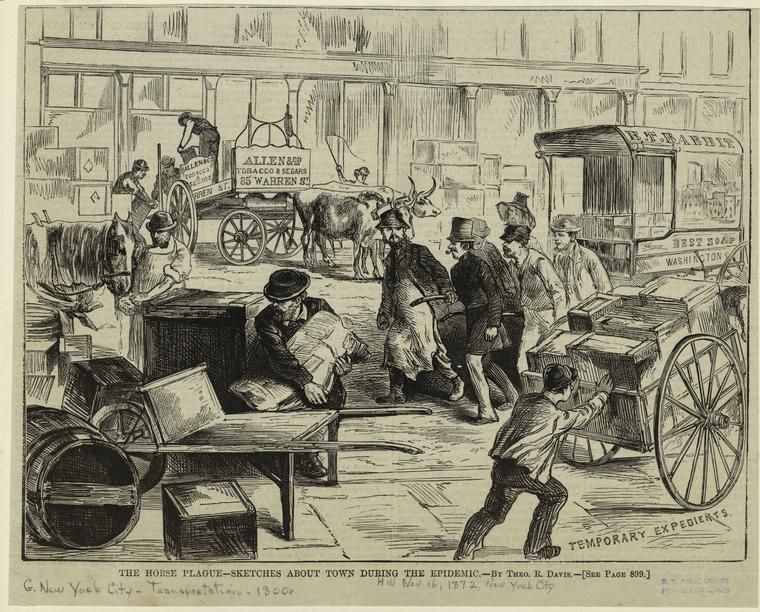

When Drake tapped crude oil, he contributed greatly to the universal turn to economic dependence on the finite supply of nonrenewable fossil fuels, beginning with coal and oil, and then natural gas. Compared to renewable fuels like wood, fossil fuels have such concentrated energy that they build economies and nations quickly by saving enormous amounts of human labor. I recently heard that for every person in America, the energy we consume is equivalent to the labor of 100 people working for each one of us full-time! This potential did not elude the captains of the Industrial Revolution, who quickly tapped into this new and seemingly inexhaustible source of energy. Along with the refining of gasoline and diesel from crude oil came the internal combustion engine, superseding the wood-fired steam engine and becoming our largest consumer of fuels derived from crude oil. 3

Aside from the big fossil fuel guzzlers like automobiles, home heating, air conditioning, lighting and food production, today we are increasingly surrounded by and dependent on labor-saving electrical devices as the mark of civilization. I recently realized this late one evening when darkness had settled over our home and I could hear the lonely call of the whippoorwill outside my window. As I turned off the house lights, I looked around and noticed our home was aglow with little green and red lights! Lights on the computer, lights on the oven. Lights on the alarm clock. Lights on the telephone and refrigerator. Lights on the smoke detectors and battery charger. Gadgets everywhere, drinking up electricity night and day, whether in use or not.

We have come to rely on Drake’s crude oil as our cheapest and most available energy source. But considering the argument being made by more and more people today, that we are running out of and being drawn into political conflicts over this cheap source of energy, it seems that Drake let the petrol genie out of the energy bottle, and there does not yet seem to be an effective incentive or initiative to get it back in. And if there is any hope to reverse this trend at all and avoid what many predict is a looming global energy shortage and accompanying political crises, the cure may well have to arise on a grassroots, individual level.

The question is, what meaningful steps can we take as individuals and families to free ourselves from Drake’s unsustainable oil, which has so insinuated itself into our lives as to seem indispensable? We can start in little ways . . . from the ground up. Over thirty years ago, our community began such an exodus from the suburbs of New York City, with backyard, postage-stamp-size gardens, abiding by the premise that we should not “despise the day of small beginnings.”

Here are some simple beginning steps you might consider:

- Start a garden in your back (or front) yard, or secure a plot in a local community garden. Maybe you can even raise a surplus so you can then learn the art of food preservation, like canning and drying.

- Start a compost pile. (Confine this venture to your backyard.) You will be making the best free fertilizer for your garden.

- Learn to sew your own clothes and/or learn to knit.

- Learn to cook; get away from pre-packaged foods and eat simpler with local foods in season.

- Hang your laundry out to dry on a good old-fashioned clothesline and skip the clothes dryer. One of my friends who does this says that her family’s clothes actually last noticeably longer.

- Bake your own bread, “the staff of life,” and use whole grains so you can really lean on that staff. Few foods can rival the taste and satisfaction of fresh-baked bread.

- Take every opportunity to walk or ride a bicycle instead of driving your car.

And once you begin to put one foot in front of the other, don’t stop. When you’ve gained this ground, move on and seize more territory. Do you really need that dishwasher? I enjoy helping wash the dishes because it is an opportunity to talk with my daughters. If you have enough land, get a milk goat or small breed cow like a Jersey and make your own butter, yogurt and cheese. Be adventurous and get a few chickens for eggs and meat. And consider even bigger leaps, like starting a cottage industry.

In the process, you’ll be lifting yourself up from a sedentary, unsustainable life. You’ll no longer need that membership at the gym since you’ll be burning calories working in the garden, doing dishes, churning butter and pedaling your bicycle. The money you’ll save at the grocery store, gas pump and in gym membership dues will ease your credit card debt, while you and your family will feel invigorated and accomplished. And though you may not get a historical marker erected at the center of town in your name or save any endangered sea creatures, you and your family will be on the road to freedom and fulfillment as you provide for your own essentials . . . and you’ll have a whale of a time along the way!